Despite my best efforts, I’ve failed to reverse the arrow of time; I continue to get older every day. I don’t feel bad about this—Stephen Hawking hasn’t licked the problem either, and, well, he wrote the book!

You don’t have to be Hawking to know what I mean. Anybody old enough to think about age can probably feel its effects in their bones. And tendons and ligaments and muscles. If you’re a runner (I am… just ran the first trail race of the year today), then you know the saying that goes “it’s not the years, it’s the mileage” isn’t really true. It’s both.

Is this getting too personal? Let’s see if I can bring it back around to anthropology: Our bones are pretty much the only things that will leave a fossil trace, and then only if the conditions are just right. If you want to stick around for a long time, you’re better off picking some other process. The chances of that are at least as slim as fossilization, but let’s pretend Massachusetts and Michigan (where Maris and I live) experience some surprise volcanic activity someday and the Boston and Detroit metropolitan areas are the 21st century’s Pompeii East and Pompeii (Mid)West. Will people know us by our bones?

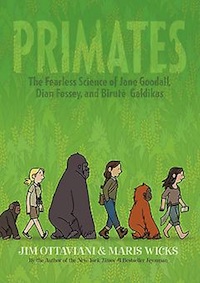

I doubt it. So, what to do? There aren’t many choices, but in our case we’re lucky enough to have made some books that we think people will read even after we’re gone. The one we made together is about Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Biruté Galdikas, and—in a supporting role—Louis Leakey. He’s the one who gave “primate behavior doesn’t fossilize” as a reason why he wanted to launch three groundbreaking scientific careers.

The first was Jane Goodall’s, and since her discovery of tool use by wild chimpanzees knocked humans off that particular pedestal she’s become one of the most famous scientists on the planet. Since that discovery, we humans have had to constantly move the goalposts in terms of defining what makes us unique. In a post-Goodall world, we’re just… not so special as we thought. And Dr. Goodall’s own humility and humanity reminds us that this is something to celebrate, not mourn.

Dian Fossey’s legacy is as much in conservation as it is in anthropology, but her work with mountain gorillas is still cited today, years after she began her research. Their gentle nature and their vanishing habitat would probably be unknown had she not sacrificed her career, her health, and ultimately her life in an attempt to protect these gorillas, our kin.

And where everyone else in history had failed to conduct short-term—much less long-term—studies of orangutans in the wild, Biruté Galdikas has succeeded. Force of will barely begins to describe what it took to do that; wild orangutans are, at their most social, uninterested in being around us, and if you manage to find them they hate being watched. (We shouldn’t take it personally. They don’t seem to like being around other orangutans all that much either.) Galdikas somehow managed to rack up days, weeks, and months of observation, where previous researchers had only managed minutes. And like Goodall and Fossey, she too has added conservation to her job description… as if being a scientist weren’t enough.

Together, these three scientists showed us how unique we are as humans (not so much as we once thought), pioneered anthropological techniques (some of which aren’t for the faint of heart, like chimp feces analysis), and inspired millions by the example they set in the wilds of Africa and Indonesia.

Their work can’t fossilize because their work won’t die.

Ideas and knowledge are wonderful like that. So while Leakey was right to say behavior doesn’t fossilize, the good news is that, at least when it comes to human behavior, it doesn’t have to.

Another quote, this time from Woody Allen: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work. I want to achieve it through not dying.”

He’s not going to get what he wants, but he’ll live on for many years via his books and films after he stops living on in his body. Our fellow primates, on the whole, don’t leave behind movies or graphic novels and Stonehenges, much less Voyager 1 spacecrafts and radio broadcasts that are on their way to nearby stars. So we should learn what we can from the chimpanzees and gorillas and orangutans (and bonobos too) while we have the chance, because despite the best efforts of Goodall, Fossey, Galdikas, and those who have followed them, we may be running out of time.

It doesn’t have to be like that. Homo sapiens is unique among the primates in that we can change the direction of that particular arrow, at least in one sense: It’s not inevitable that our children will only be able to know about orangutans or mountain gorillas or chimpanzees via books and movies and an occasional visit to a zoo. We’ve proved with other species that we can slow down the march towards extinction, and even reverse it. It’s hard, but it’s worth it. And these chimpanzees, these gorillas, these orangutans…these really are our kin, and making sure they travel with us into the future will leave a legacy of humane behavior that even the most perfectly preserved fossil can never match.

It doesn’t have to be like that. Homo sapiens is unique among the primates in that we can change the direction of that particular arrow, at least in one sense: It’s not inevitable that our children will only be able to know about orangutans or mountain gorillas or chimpanzees via books and movies and an occasional visit to a zoo. We’ve proved with other species that we can slow down the march towards extinction, and even reverse it. It’s hard, but it’s worth it. And these chimpanzees, these gorillas, these orangutans…these really are our kin, and making sure they travel with us into the future will leave a legacy of humane behavior that even the most perfectly preserved fossil can never match.

And when we do that, we’ll prove Louis Leakey’s quote wrong. Or at least irrelevant.

He’d be happy about that.

Image of Suchomimus on Display at the Royal Ontario Museum by Wikimedia Commons user Captmondo.

Jim Ottaviani has written nonfiction, science-oriented comics since 1997, notably the number one New York Times bestseller, Feynman and Fallout which was nominated for an Ignatz Award. He has worked as a nuclear engineer, caddy, programmer, and reference librarian. His most recent book, Primates is his first collaboration with artist Maris Wicks; The New York Times says of it, “Primates is the kind of book that can produce new scientists.” He lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.